VIRTUAL IMPERATOR, EDGE OF EMPIRE: Shaun Gladwell

On the occasion of ACP’s latest exhibition Virtual Imperator, Edge of Empire by renowned artist Shaun Gladwell, Dr. Bill Schaffer gives an in-depth insight into the artist’s approach to warfare.

War has been a recurrent theme of Gladwell’s work since he was commissioned by the Australian War Memorial (AWM) in 2009 to spend three weeks embedded with troops serving in Afghanistan. Since that pivotal episode in his career, Gladwell has returned to the theme in different contexts, using a variety of different media, including paint, video, photography, installation, and 360° video.

There is a photograph held by the AWM that shows Gladwell fully outfitted in military armour during his time in Afghanistan. He looks directly at the camera and smiles broadly. He seems surprisingly happy, even content. One can speculate about the reasons for his apparently buoyant mood in such a heavy setting. My guess is that Gladwell seems so pleased because the experience of wearing military armour in its ‘proper’ setting is essential to his project as an artist of war.

The military is a system geared around the need to prepare human bodies for violent conflict. Soldiers are taught are not to expect recognition as individuals within that system, but only in terms of their rank in a strictly defined hierarchy. If uniforms signify the submission of individual wills to a hierarchy, armour signifies the submission of the body to a generic function in which protection exists to enable further exposure.

I think this lived relationship between human bodies and the system of the military forms the overwhelming focus of the current exhibition. The interest lies less in directly confronting the terrible and violent reality of conflict than in contemplating the behind-the-lines preparation of the body for conflict; the everyday processes by which individuals are incorporated into a functioning war machine. Wearing armour makes Gladwell smile in this context because it means putting himself inside the condition he seeks to express.

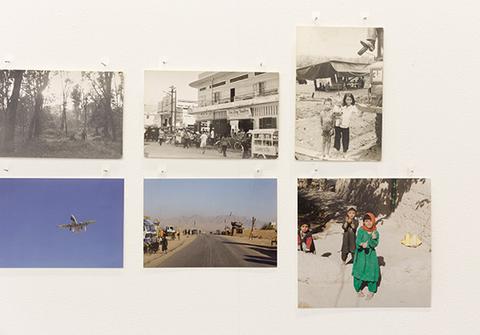

In Mark Gladwell Vietnam 1967 / Shaun Gladwell 2009, a series juxtaposing shots taken by Gladwell’s father during service in Vietnam with snaps taken by Gladwell in Afghanistan, we are invited to consider ‘coincidences’ between these two different wars. At one level, this is a deeply ‘personal’ exercise in which Gladwell draws parallels between his own life and that of his father; at the same time, the images are subject to a kind of distancing device, in the form of the criteria Gladwell employs to select them. What becomes important here is not so much the content of individual shots, as the resonances that can be recognised between them in an exercise of pattern recognition. Shots of helicopters or vehicles seem to be given the same weighting as shots of the artist’s father or the artist himself. These are not moments in which the heroism of individuals shines through the fog of war; they are presented as supremely ‘average moments’, ‘statistical portraits’ in which the interest emerges from the links between images. They seem to me like studies in ‘soldierly comportment’ that ask if it might be possible to discern a specific ‘body language’ of war, one that would be expressed not only in gestures associated with the spectacular drama of conflict, like aiming a rifle or hunkering down in a trench, but also in the subtle inflections and ‘family resemblances’ of the most quotidian gestures, like sitting, walking, or smiling.

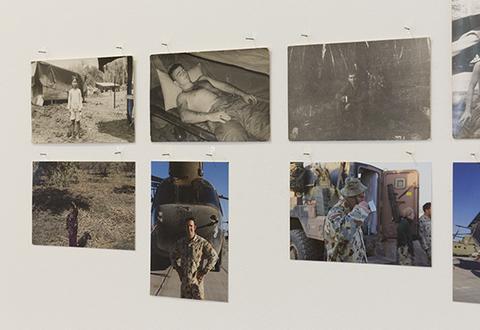

Gladwell is best known for video studies of action sports like skateboarding, BMX, parkour, etc. In a broad sense, these works are time and motion studies of bodies performing under various constraints. In this exhibition, The Sleeping Soldiers series presents fragments of a time and motion study focused on inactive bodies for which time and motion themselves are suspended. These are soldiers taken to the limit of exhaustion, seeking opportunities for rest in any available circumstance. Like Tim Hetherington’s well-known studies of sleeping soldiers, these photographs show bodies usually associated with the exercise of perpetual vigilance in a state of maximum vulnerability. Gladwell’s shots, however, have a very different feel. Hetherington presents carefully composed studies of individuals sculpted in light and shadow in order to show each soldier as ‘his mother might have seen him’. It is impossible to look at these images without noting their mastery, the sense that the soldiers’ bodies are cradled in the loving light of the camera. Gladwell, by contrast, is as much captivated by a collection of legs truncated by the frame as in the secret drama of sleeping faces. The tone is one of sampling, scanning, aggregating (probably on ‘full auto’). The interest again lies as much in what happens ‘between’ the images as in the content of individual shots, but this time in the context of a single series. Sleeping Soldiers seems to evoke the possibility of an indefinitely extended research project focused on the comportment of war that would establish a kind of ‘model sheet’ like those employed by animators, but this time applicable to a ‘universal soldier’. This sense of abstracted ‘formalism’ may be taken reflect the disciplinary functioning of the war machine itself.

Double Field/Viewfinder (Tarin Kowt) involves a kind of ‘playful’ interaction between the artist and two soldiers, themselves ‘armed’ with video cameras. It is a game of mutual anticipation that records itself as it unfolds. The field of view of each soldier is shown on opposing screens, resulting in a stereo video that shows both attempting to target the artist himself, without appearing in the viewfinder of the other. The implied effect is to leave the viewer caught in what Gladwell has called ‘image crossfire’. Each participant tries to centre the others in his viewfinder, but this very effort of centring results in a constantly decentred dynamic, a kind of dance of deferred death. The everyday activity at stake here is evidently that which begins the moment a soldier wakes from sleep: looking. A field soldier’s body is optimised and geared up for vigilance and counter-vigilance (camouflage, stealth tactics), not just through the external weight of prosthetics (binoculars, scopes) and armour, but through the internalisation of discipline. This work explores the ways that hyper-vigilance takes hold of the bodies of soldiers ‘from within’, transforming their very ‘being-in-the-world’.

AR15 is a highly ‘loaded’ piece that uses 360/VR video to show a man ‘stripping’ an assault rifle, the ‘immersive’ format allowing us to virtually ‘inhabit’ the space in which he lives and works. In so doing, it seems to play on several inescapable ambiguities and tensions. For a start, the weapon has been used in more than one incident of domestic terrorism in the US. More specifically, the performer is dark skinned, has a possibly ‘Muslim-looking’ beard, and executes his performance while blindfolded and kneeling in front of a video camera, like a victim readied for murder in an ISIS promotional video, but also in the manner of a devotee praying in the direction of Mecca. The man seen stripping the weapon seems utterly calm, almost meditative throughout the performance, which has the formal rigour of a Japanese tea ceremony. He is able to carry out this task because he has been trained to do so as a field solider (a combat medic, to be specific) in the ultimate proof that he knows his rifle ‘like the back of his own hand’ and has effectively assimilated it to his own body. At the same time, our own inability to freely navigate the virtual space we observe ‘around us’ suggests, perhaps subliminally, that we may somehow be the real captives in this scenario. The ambivalence of these colliding signs seems to undercut and complicate any sentiment of simple identification with the performer, as would be prescribed by the rhetoric of the ‘empathy machine’ which VR proselytisers have adopted in marketing their Head Mounted Displays as unprecedented generators of enhanced global consciousness.

The video footage Field Injury Simulations of combat medics working with ‘bleeding mannequins’ fed by hoses inserted between their legs, an experience we may assume must have been undergone by the performer in AR15, is certainly the most outwardly bizarre and shocking on display in this exhibition. It comes closest to the rhetoric of ‘forcing us to face the truth we do not want to face’, except that the thing we might face here – the reality of broken, bleeding bodies – is entirely absent. What we actually witness is the process by which combat medics are themselves prepared to face that terrible truth. This perhaps explains the seemingly contrived Jodorowsky-style nightmare ambience of the scene, right down to the macabre, frozen funfair grins on the faces of the dummies: the trainees are not only learning to make preliminary repairs on broken bodies, but are being ‘deliberately’ desensitised in advance to the surreal chaos and trauma of the battlefield.

Like most of us viewing this exhibition, the soldiers seen here were once ‘ordinary citizens’ who knew nothing directly about war, yet had doubtless already consumed endless images of war, whether in the form of TV news reporting, Hollywood films, or interactive games. The images Gladwell presents to us in cannot be accused of ‘glorifying war’, but they are also not anti-war’ in any obvious or didactic fashion. I think they are an attempt to acknowledge and honour a form of experience that is essential to becoming-soldier. It is an experience undergone by individuals in a system designed to protect them, but precisely as reduction of their individuality to a norm, in a context where protection exists to prolong exposure to mortal danger.

It is appropriate and moving, then, that the AR15 360° video is accompanied by a bar of Maxwell’s Soap, which the performer in the piece personally fashions from the finest ingredients, donating one bar to a homeless person (many of whom may be veterans) for every bar he sells. This seems to be at once a kind of personal trauma therapy and a sort of humble political activism insisting upon the absolute significance of the most banal bodily acts of daily self-care.

About the writer

Dr Bill Schaffer is an academic, writer, and skateboarder who has collaborated with Shaun Gladwell on several projects, both as performer and writer. He has published widely in the fields of film studies, cultural studies, philosophy, and art history. His doctoral thesis addresses the uses of violence in film, including war films. Schaffer is currently completing an M.A in Curating and Cultural Leadership at UNSWAD.

Exhibition details:

ACP Project Space Gallery from 17 March to 6 May 2017

Images

Shaun Gladwell, Field Injury Simulations, 2017. © the artist. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery.

All installation images © ACP Michael Waite

Shaun Gladwell, AR 15 Field Strip 2016, 360 virtual reality videowork with sound. Cinematographer: Judd Overton / Production: Badfaith VR. Courtesy The Gene & Brian Sherman Collection, Sydney

Shaun Gladwell, Field Injury Simulations, 2017. © the artist. Courtesy the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery.

Courtesy and © Maxwell’s Soaps

Shaun Gladwell Field Injury Simulations, 2017. Courtesy © the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery.

Shaun Gladwell Field Injury Simulations, 2017. Courtesy © the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery. Shaun Gladwell Afghanistan 2009. Courtesy © the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery.

Shaun Gladwell Afghanistan 2009. Courtesy © the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery. Installation View

Installation View Installation View

Installation View Installation View

Installation View Installation View

Installation View Installation View

Installation View